Why being a situational leader works so well

Why being a situational leader works so well

Have you ever experienced being micro-managed? Or perhaps being left alone when you didn’t know what to do. Maybe you’ve felt stifled or even patronised by your manager. These are traits of a manager who could benefit from becoming a situational leader, i.e. providing the style of leadership you need rather than the style they prefer.

Becoming a situational leader is a key skill to learn for anyone who wants to enable their teams to thrive. A situational leader takes time to define the goal (i.e. what needs to be done) and then identifies the levels of competence and commitment to achieve the goal. A situational leader then matches their leadership style to the needs of the team member to avoid micro-managing, patronising, suffocating, or going AWOL. Becoming a situational leader means that a team member is directed and supported in a way that enthuses and energises. It zaps instead of saps.

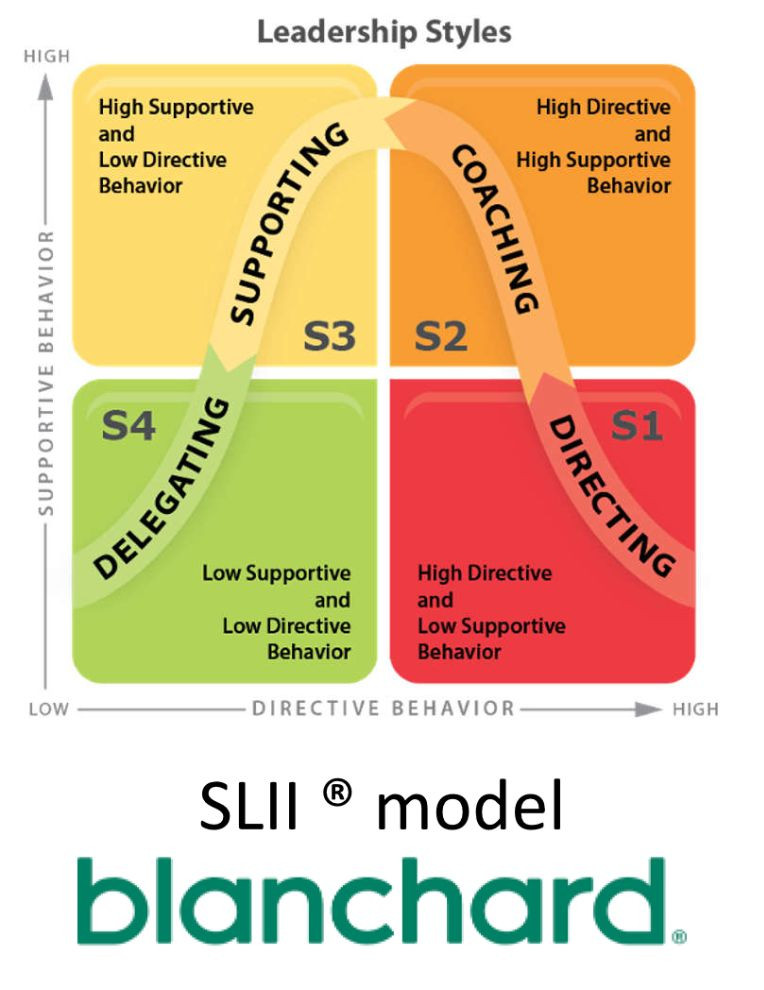

At Beyond Theory we use the SLII® model in our Leadership Behaviours training. It gets rave reviews. Here’s how it works:

Step 1 – Set the goal.

We advocate using SMART as a way of setting goals. In a nutshell, SMART goal setting is very much about being specific about the goal and when it’s to be completed, along with working with the team member’s motivations to achieve what needs to be done. You can learn more about this method in our blog Be even SMARTer with your SMART goal setting.

Step 2 – Diagnose your team members needs

Using SLII requires you to stand back and assess where your team member is in terms of competence (i.e. skills and knowledge to complete the task) and commitment (i.e. motivation and/or confidence to complete the task). This is a critical step, as making assumptions can be very damaging to all concerned. Please remember that levels of competence and commitment need to be correctly identified for each task or goal. Situational leadership is task or goal specific and not person specific.

Levels of competence and commitment can vary depending on the task or goal to be achieved. These levels influence how the team member will approach the task. SLII places each of these stages into four development levels.

For example, a team member with low competence yet high commitment is defined as an enthusiastic beginner i.e. ‘I want to do what you are asking me but I don’t know how to make a start. Please tell me’. They are at the enthusiastic beginner stage – Development Level 1 (D1).

A team member who has some competence but low commitment is described as a disillusioned learner. They are at Development Level 2 (D2). An example of someone who has reached this level could be a team member who is feeling overwhelmed about what they need to do. Their commitment will have dropped as a result because they are struggling as they try to build their competence but feel that they cannot cope. This some competence and low commitment phase is critical. Those who feel this way are in danger of quitting – not just the task but maybe even the job.

Development Level 3 (D3) is reached when an employee has high competence to achieve a task but their commitment is variable. Because they know what to do yet their motivation and/or confidence fluctuates, team members at this stage are described as reluctant or cautious contributors. A team member at this level of competence and commitment may be someone new to a task. Conversely, they may be someone who has high competence but has lost interest and/or motivation in doing what they have been asked to do.

Team members who can reliably complete a task because of their high competence and high commitment have reached Development Level 4 (D4). These can be referred to as peak performers. They don’t need much in direction and support. Of course, as with all of the other development levels, goals need to be set and agreed with peak performers. However, it’s more like 'Tell me when you done it' rather than 'I’ll tell you what to do and when you need to do it by'. Keeping peak performers occupied can be a challenge – as is the need to avoid overloading them as they are so reliable. Overworked and under-appreciated peak performers can quickly become reluctant contributors when they lose their motivation to use their high competence.

Step 3 – match your leadership style to meet the needs of your team member

This is when the magic happens.

The SLII model offers a situational leader four different leadership styles to use. Based on the amounts of direction and support used, the four options are Directing – Style 1 (S1), Coaching – Style 2 (S2), Supporting – Style 3 (S3) and Delegating – Style 4 (S4). More about these styles later.

First let’s discover what being directive and supportive means.

Directive behaviour is about structuring, teaching, organising and supervising. Examples of being directive is setting goals, showing team members what good looks like. Being directive is about frequent communication on progress. When it comes to SLII, directive behaviour is not about finger wagging or, in the extreme, bullying. Directive behaviour builds competence.

Supportive behaviour is more about two-way communication. It’s about asking, listening, explaining and encouraging. Examples of supportive behaviour are listening and sharing information. Being supportive is also about explaining rationale and solving problems together. Supportive behaviour addresses motivation and/or confidence.

By mixing and matching directive and supportive behaviour the SLII model provides four leadership styles. Each are equally valid, depending on the needs of the team member for each particular task.

Directing – Style 1 (S1)

As a situational leader this style uses high directive behaviour and low supportive behaviour. The emphasis is on setting goals, showing how things need to be done and discussing progress. Directing is very much about setting priorities and providing clarity on boundaries. There is some degree of supportive behaviour but directive behaviour is primary.

Directing (S1) is to provide what an enthusiastic beginner (D1) needs. Directing addresses the need to build competence. In these circumstances applying a directing style will be an effective match.

Coaching – Style 2 (S2)

In terms of being a situational leader, this style uses both high amounts of directive and supportive behaviour. This style is still building competence but also addresses commitment issues. Coaching explores concerns and provides encouragement. This leadership style also works jointly on problems whilst providing information and perspective.

Coaching (S2) is to give what a disillusioned leader is needing. Coaching continues to build competence yet at the same time focuses on the motivational and/or competence issues a team member is facing. This is why using a coaching style will be effective.

Supporting – Style 3 (S3)

This style of leadership is less about building competence but focusing on the commitment issues that a team member may be facing. For example, a drop in motivation or a lack of confidence. Supporting focuses on listening and encouraging rather than teaching and supervising.

Supporting (S3) is to provide the levels of support and direction that a reluctant or cautious contributor needs to complete their task. A little direction is needed (such as goal setting etc.), but the majority of a situational leader’s energy in these circumstances is to be asking, listening, explaining and encouraging.

Delegating – Style 4 (D4)

When using this style of leadership only limited amounts of directive and supportive behaviours are needed. Delegating needs to encourage and sustain a team members autonomy to complete a task. Of course, communication and checking-in is necessary but will be less frequent. A situation leader using Delegating needs to let go.

Delegating (D4) gives the freedom within a framework for a peak performer to be at their best. It’s not so much about building competence and commitment as these are already high with such a team member. It’s more about keeping the peak performer performing. Do not over-burden or burnout a peak performer.

Summary

Being a situational leader works. However, being a situational leader is not easy. It takes time and effort to understand the needs of your team members, for each and every task they undertake. Although it’s different strokes for different folks, being a situational leader also recognises that it’s different strokes for the same folks.

To learn how to become a better situational leader please visit our Leadership Behaviours page. We are an approved channel partner with Blanchard, the owners and publishers of SLII and are licensed to use their world class materials on our training. It is with their permission we use their image of the SLII model.

Paul Beesley

Director and Senior Consultant, Beyond Theory